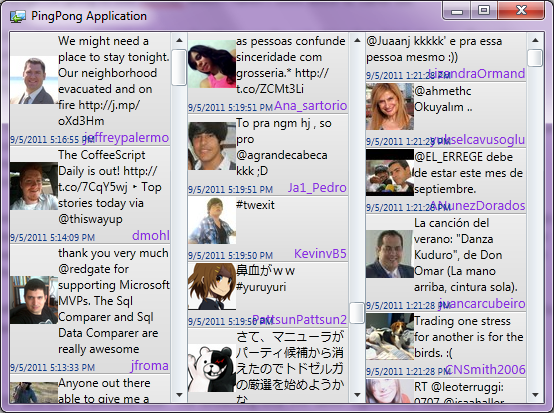

This is going to be the last post that concludes my series on building a real-time push app with Silverlight. Any additional posts would likely be outside the context of writing a push app and more about how I’m adding features to ping.pong, my Twitter app, so I think this is a good place to wrap up and talk generally from a top down overview of building a push-style application.

Here’s a recap of everything discussed so far:

Part 1: Basics – Creating an Observable around a basic HTTP web stream against Twitter’s streaming API

Part 2: Subscription and Observation of Observables

Part 3: Basics of UX design with a look at shadows and gradients.

Part 4: Integrating with 3rd party libraries, notably Caliburn Micro and Linq2Twitter and how to achieve polling with observables.

Part 5: A minor hick up with Linq2Twitter.

Part 6: Taking advantage of transparencies to improve the design and reusability of UX.

Part 7: A summary of all things encountered so far, replacing Linq2Twitter with Hammock, first release of code to GitHub, and a binary released capable pulling and streaming tweets from Twitter.

Part 8: Examples of using Caliburn Micro to easily resolve data bindings that otherwise would be much more effort.

And that leads us to this post…

PDD (Push Driven Development)

One of the main goals of this series is to create a performant Silverlight app based on push principles, as opposed to more traditional pull principles. To that effect, ping.pong has performed remarkably well and is limited only by Twitter’s throttling, which currently appears to be maximum of 50 tweets per second via the streaming API.

Writing the application from a push-driven mindset was definitely unintuitive at first, and I had to refactor (actually rewrite is more accurate) the code many times to move closer to a world where the application is simply reacting to events thrown at it (as opposed to asking the world for events).

To be absolutely clear on what I mean on the differences between push and pull, here’s a comparison:

| Pulling | Push |

| var e = tweets.GetEnumerator(); while (e.MoveNext()) // is there more? { e.Current; // get current DoSomething(e.Current); } | IObservable<Data> data = /* get source */ // whenever data comes, do something data.Subscribe(DoSometing); |

On the pulling side, the caller is much more concerned with the logic on how to process each message. It needs to repeatedly ask the world, “hey, is there more data?”.

On the push side, the caller merely asks the world, “hey, give me data when you get some”.

Twitter is a perfect example because their APIs have both a pulling and pushing models. Traditional clients poll continuously all the time, and many had configurable options to try to stay under the 200 API calls per hour limit. Most of Twitter’s API still consists of pulling, but the user’s home line and searching can be streamed in near real time via the streaming API, aka. push. Streaming tweets effectively removes the API call limit.

Push and Pull with Reactive Extensions

The beauty of Rx is that regardless of whether it is actually pushing or pulling, the API will look same:

IObservable<Tweet> tweets = _client.GetHomeTimeline();

tweets.Subscribe(t => { /* do something with the tweet */ });As far as the caller is concerned, it doesn’t care (or needs to know) whether the GetHomeTimeline method is polling Twitter or streaming from Twitter. All it needs to know is when a tweet comes it will react and do something in the Subscribe action.

In fact, Subscribe simply means “when you have data, call this”, but that could also be immediately, which would be analogous to IEnumerable.

However, if that was the only thing Rx provided it wouldn’t be as popular as it is, because other pub/sub solutions like the EventAggregator already provide a viable asynchronous solution.

Unlocking Rx’s power comes with its multitude of operators. Here’s an example:

public static IObservable<Tweet> GetStreamingStatuses(this TwitterClient client)

{ return client.GetHomeTimeline().Merge(client.GetMentions())

.Concat(client.GetStreamingHomeline());

}

GetHomeTimeline and GetMentions initiate once-only pull style API calls, while GetStreamingHomeline will initiate a sticky connection and stream subsequent tweets down the pipe.

The Merge operator is defined as this: “Merges an observable sequence of observable sequences into an observable sequence.”

I think a better description would be “whenever there is data from any of the sources, push it through”. In the example above, this would translate to whenever a tweet comes from either the home timeline or the mentions timeline, give me a Tweet (first-come-first-push), followed by anything from the streaming timeline.

And there lies one of the greatest beauties of Rx. All of the complexity lies solely on setting up the stream and operators. And that, also, is its disadvantage.

Rx Complexity

Let’s take a look at the Concat operator, defined as: “Concatenates two observable sequences.” In the remarks sections it states this: “The Concat operator runs the first sequence to completion. Then, the second sequence is run to completion effectively concatenating the second sequence to the end of the first sequence.”

Let’s try it out:

var a = Observable.Interval(TimeSpan.FromSeconds(1)).Select(x => x.ToString());

var b = Observable.Interval(TimeSpan.FromSeconds(1)).Select(x => "s" + x);a.Concat(b).Subscribe(Console.WriteLine);

// output: 0, 1, 2, 3, 4...

As expected, only numbers are printed because the first sequence never ends, so it won’t concatenate the second one. Let’s modify it so that it does finish:

int count = 0;var a = Observable.Interval(TimeSpan.FromSeconds(1))

.TakeWhile(_ => ++count < 5)

.Select(x => x.ToString());

Note, that using Observable.Generate is preferred because it doesn’t introduce an external variable, but I stuck with Interval so the code looks similar to the second observable. As expected again, it will print “0, 1, 2, s0, s1, s2”.

OK, let’s spice things up. Let’s make b a ConnectableObservable by using the Publish operator, and immediately call Connect.

int count = 0;var a = Observable.Interval(TimeSpan.FromSeconds(1))

.TakeWhile(_ => ++count < 5)

.Select(x => x.ToString());

var b = Observable.Interval(TimeSpan.FromSeconds(1)).Select(_ => "s" + _).Publish();b.Connect();

a.Concat(b).Subscribe(Console.WriteLine);

What do you think the output of this will be? The answer is “0, 1, 2, 3, s5, s6, s7, …”

Despite using the same Concat operator, the result can be very different depending on the source observables. If you use the Replay operator, it would have printed “0, 1, 2, 3, s0, s1, s2, …”

Years and years of working in synchronous programming models have trained us to think in synchronous ways, and I picked Concat specifically because Concat also exists in the enumerable world. Observable sequences are asynchronous, so we never know exactly when data comes at us, only what to do when it does. And because streams occur at different times, when you combine them together there are many many ways of doing so (CombineLatest, Merge, Zip, are just a few).

The greatest hurdle to working in Rx is to know what the different combinations do. This takes time and practice. RxTools is a great learning tool to test out what all the operators do.

Unit Testing

Last but not least, Rx can make it easier to write unit tests. The concept is easy: take some inputs and test the output. In practice this is complicated because applications typically carry a lot of state with them. Even with dependency injection and mocking frameworks I’ve seen a lot of code where for every assert there is 10 lines of mock setup code.

So how does it make it easier to test? It reduces what you need to test to a single method, Subscribe, which takes one input, an IObservable<T>.

Conclusion

Rx is a library unlike any other you will use. With other libraries, you will add them to your solution, use a method here or there, and go on with your life. With Rx, it will radically change the way you code and think in general. It’s awesome.